Zora x Sinners (Part 2)

The Women Who Fight, the Spirits Who Wander: Rootwork, Resistance, and Reckoning

Welcome back, family. If you missed Part 1 in this series, gone head and check that out first. Then meet us right back here.

Now on to Part 2…

Before we talk about the women who fight, we have to talk about what they were fighting through.

It wasn’t just white supremacy. It wasn’t just poverty. It wasn’t just patriarchy.

It was also the spirit world: the dead who wouldn’t stay dead, the haints who wouldn’t leave you be, the unsettled forces looking for new flesh to climb into.

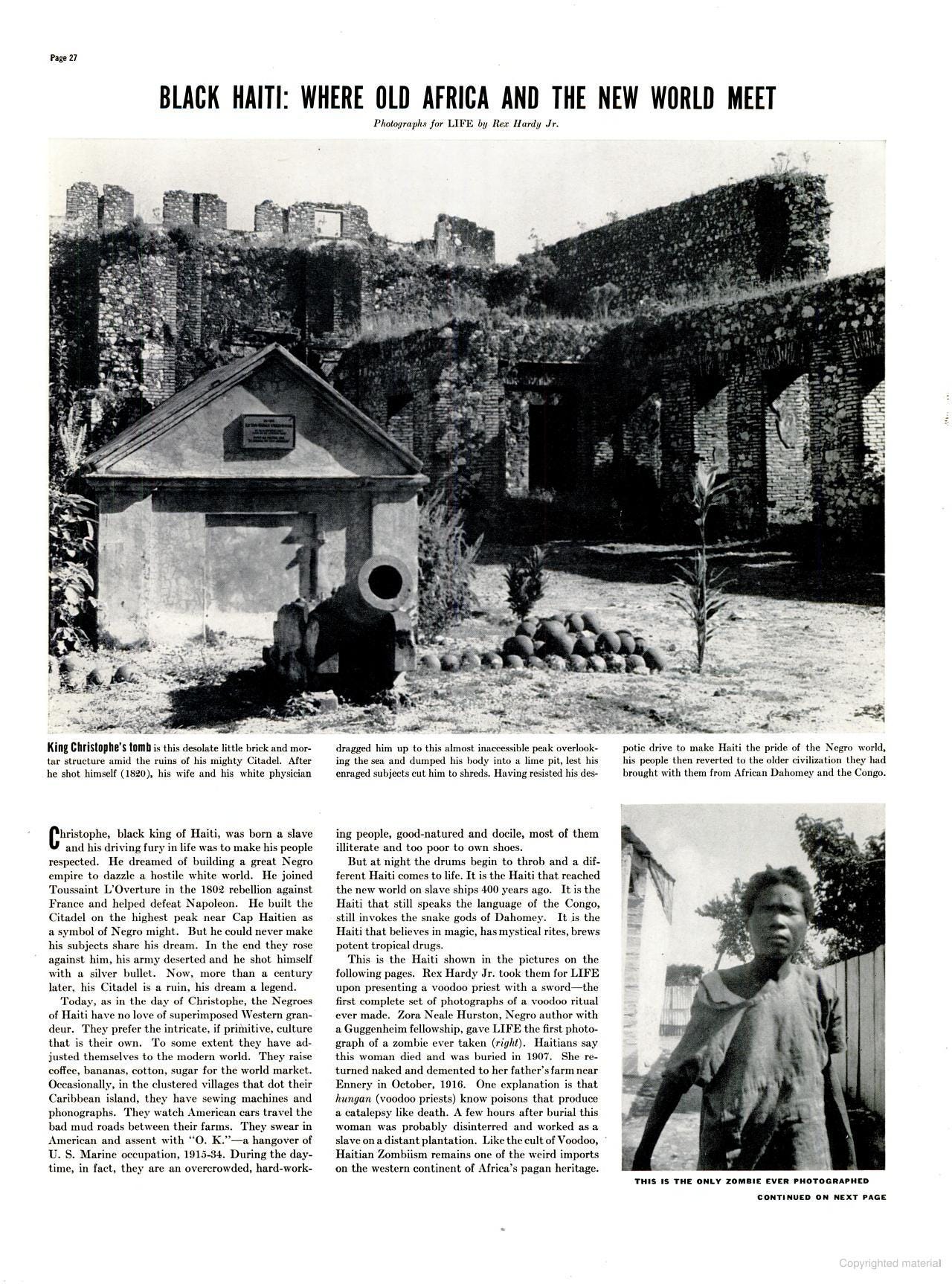

Zora Neale Hurston spent a lot of years absorbing tales of such things. She recorded it too with a level of reverence other anthropologists couldn’t and wouldn’t come close to. The fact is a lot of that was on purpose. But as a trained anthropologist and daughter of Eatonville, Zora was collecting folktales and real testimony. Not only did she collect, she witnessed serious, sacred knowledge from those who lived in close relationship to the unseen world.

Now she wasn’t for that objective, observe-at-a-distance fieldwork neither. She got up close and real personal — like the time she captured the first zombie to be caught on camera through her very own lens in Haiti. I ain’t kidding either. Just read her book Tell My Horse (page 138) or Google "Felicia Felix-Mentor."

In Tell My Horse, Zora tells us folks was awakenin’ the dead to have labor that ain’t cost a thing (cue that scene of Cornbread and his wife sharecroppin’ and the chain gang for proof slave master mentality ain’t neva ended) and to do they thievin’, too.

But Zora’s dance with the spirit world started well before her trip to Haiti as a two-time Guggenheim Fellow in 1936 and 1937.

In Mules and Men (1935), she wrote:

"All over the South and in the Bahamas, the spirits of the dead have great power, which is used chiefly to harm."

(Mules and Men, p. 227)

These spirits could cross thresholds (when invited), could slip through dreams (even uninvited), could reach out from grave dirt still warm with old sins and hostility.

And the people knew it. They knew how powerful graveyard dust could be.

Zora dropped the knowledge:

"Dirt from sinners' graves is supposed to be very powerful, but some hoodoo doctors will use only that from the graves of infants. They say that the sinner's grave is powerful to kill, but his spirit is likely to get unruly and kill others for the pleasure of killing."

(Mules and Men, p. 228)

Think about that. Not every spirit you call up is gon' listen. And the ones you call ain’t always gone let you be the boss. Some cut themselves loose and just go on having their way.

Lucky for us, Zora is gonna be thorough if nothin’ else. So she tells us that there are old tried and true protections. Many of them our grandparents and parents did or do, even if they don’t tell us why:

"This is why a cloth is thrown over the face of a clock in the death chamber, and a looking glass is covered over. The clock will never run again, nor will the mirror ever cast any more reflections if they are not covered, so that the spirit cannot see them."

(Mules and Men, p. 228)

The Spirits of Sinners

Now tell me that don't sound like what we saw in Sinners.

Tell me that ain’t the vampires emerging like the slow crawl of patient white smoke, twistin' their way through sorrow and survival, sellin' a dream of freedom.

In Sinners, the spirits are restless, angry, unfinished, but only after tryin’ to seduce with song, dance, and a promise of equality. And that’s exactly what Zora’s field teachers was schoolin’ her on.

So when Annie works her root and gives her man that mojo bag, when folks feel the remnants of grave dust in the air, when it’s uttered that something "ain't right," baby, they ain't spookin'. They’re naming a reality Zora knew intimately and many of us know ancestrally even if the language and conscious of mind is lost to us.

Big Sweet = Annie: Our Protectors in Plain Sight

But there is divine covering carried in the ones who remember or answer the call. If you lucky, you got yoself one and she a lot like Annie.

Annie is a gorgeous character in Sinners that represents an archetype history (and the present) tries to erase. No doubt Annie was crafted in reverence.

(I mean, can we hear it for whoever was consulting on this film, ‘cause whew! Ryan and his team did NOT miss!)

On that screen, we are gifted with Annie’s loyalty, her passion, her sensuality, her grief, her ancestral wisdom, and her matriarchal love.

She gives us her "and ain’t I a woman?" too… (Yasss to that scene with Michael, Lawd!)

Annie is steeped in her knowledge in the roots, and her unshakable faith. When she gave that baby girl some High John the Conqueror for her mama, I knew I would feel Annie on so many levels of appreciation, especially since Zora taught me ‘bout the myth, the man, and the “medicine.”

Now in Sinners, Annie is the one who declares the fight and guides the others in how to do it with the kind of strength and spirit that feels ancient and familiar all at once.

I can’t lie, that gave Lucy Potts Hurston (Zora’s mama) when Annie made them folks eat that garlic.

It also reminded me of Big Sweet, the real woman Zora met and befriended during her fieldwork in a Florida work camp in the late 1920s.

Big Sweet wasn’t just tough; she was a living monument to loyalty and courage.

She also ain’t play dat, just like Annie.

As Zora wrote in Mules and Men:

"I knew that Big Sweet didn't mind fighting, didn't mind killing, and didn't too much mind dying."

(Mules and Men, p. 150)

When violence threatened, it would’ve been easier for Zora to leave.

But Big Sweet’s fearlessness pulled somethin’ out of her; a bravery she didn’t even know she had. Even though Zora was a tomboy and grew up givin’ her brothers and the boys of Eatonville hell, work camp life was real different. A fight to the death was a common thing and wasn’t no jokin’ about it.

Zora learned that first hand:

"I thought of all I had to live for and turned cold at the thought of dying in a violent manner in a sordid saw-mill camp. But for my very life, I knew I couldn't leave Big Sweet even if the fight came. She had been too faithful to me. So I assured her that I wasn't going unless she did. My only weapons were my teeth and toenails."

(Mules and Men, p. 150)

Annie in Sinners walks in Big Sweet’s sacred footsteps, channeling the ancestors and her own spirituality for the fight of her life.

Annie inspires Smoke to choose courage over kin — because Stack wasn’t really Stack anymore, but the mind and heart are powerful things.

She got the rest of them together, too. Said we gon' fight if they get in here, which they did thanks to Grace.

Through her leadership, Annie reminds us that courage is contagious when it’s rooted in the ancestors, intention, and radical love. I truly had chills when Annie said she had somebody waiting on the other side for her and Smoke did too.

I hope that every one of us carries someone like Annie and Big Sweet in our blood memory. The ones who teach us that Black womanhood is layered, luminous, brave, wise, and wholly divine.

Music as Portal: The Guitar, the Harmonica, and the Gathering

Music ain't just background noise in Sinners.

It’s a character.

It’s a portal.

It’s a witness.

Sammie's guitar hums like it knows more than it says.

Delta Slim’s harmonica cuts through the air like a sermon at a crossroads.

And when he hits them keys… those who felt it know.

The embodiment of music in this film ain’t an accident. It’s as much a moving, evolving contributor just like the setting of Eatonville in Zora’s novels, short stories, and plays.

Like Ryan and his team, Zora Neale Hurston understood music not as decoration, but as invitation. An ancient doorway into story, memory, and truth.

When she traveled through the work camps, the jook joints, and the fields gathering folklore, she didn’t just sit down and ask folks to talk.

(I mean, she tried to at first, but learned quick, quick how ineffective that was.)

Zora tapped into her culture to find a way that no academic could teach her.

She sang first.

She played first.

She met the people where the spirit was moving.

In Dust Tracks on a Road, she wrote:

"Polk County. After dark, the jooks. Songs are born out of feelings with an old beat up piano, or a guitar for a mid-wife."

(Dust Tracks on a Road, p. 83)

Music wasn’t optional.

It was survival.

It was testimony.

It was the way the body said what the tongue sometimes couldn't.

Sammie, Delta Slim, and Pearline are in conversation with Zora and the folks she met in America's South through their music, through their blues, through their instruments.

Zora is also in conversation with Ryan too as they crafted their respective characters. Tea Cake and Janie. Sammie and Pearline. It’s a seduction in both cases.

"She heard somebody humming like they were feeling for pitch and looked towards the door. Tea Cake stood there mimicking the tuning of a guitar. He frowned and struggled with the pegs of his imaginary instrument watching her out of the corner of his eye…Finally she smiled and he sung middle C…"

(Their Eyes Were Watching God, p. 100)

Tea Cake even plays outside Janie’s door, in the jook joint (when he stole Janie’s money), and on the muck. Even when Janie buries the man, she buys him a guitar and puts it in his hands to carry with him into the after life. I think Janie would give Pearline a knowing look, even in passing. One that says, ‘girl, I get it!’

Zora’s Harmonica and Guitar: Tools of Trust

Now, I must tell you that Zora didn’t just carry notebooks into the field.

She carried a harmonica and a guitar too.

(I had the privilege of revealing this fact to her nephew — yes, by blood — back in 2023. He is a musician!)

Because she knew:

Before you get a story, you gotta create a circle.

Before folks give you their memories, you gotta give them your music.

She would play or lend her instruments out.

Folks would gather.

The air would soften.

Feather-bed resistance vanished.

Then — and only then — the stories would come.

Fannie Hurst (author of Imitation of Life) remembered:

"Zora—‘all greased curls, bangles, and slashes of red’—usually presided over the festivities with her harmonica and her head full of stories."

(Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston, p. 121)

Zora was just like Sammie’s guitar in Sinners — gatherin’ the town, remindin’ them that they were alive, passionate, and formidable even when the world, vampires, and the Klan tried to wring them dry.

Just like Delta Slim’s harmonica carried sorrow and sweetness side by side, Zora was in the work camps with “the Negro lowest down” who embodied art and tragedy simultaneously. She sat to hear their songs and stories passed through the mouths of generations, known and unknown. And, of course, she gave ‘em hers too.

Music as a Spirit Carrier

The music in Sinners ain’t just pretty.

It’s carrying somethin’.

Somethin’ old.

Somethin’ heavy.

Somethin’ holy.

Every pluck of Sammie’s strings, every wail of Pearline’s voice is another line of prayer stitched between the living and the dead.

It’s another reminder that even when words fail us, the sound of survival still rises up.

Just like Zora reflected back to us on the page:

We must sing and play our instruments.

Because it is remembering.

It is resisting.

Our music is reaching for the unseen and pulling it back down into our hands.

And if you need proof, just check out that brilliant montage of African diasporic cultures weaving a tapestry of rhythm and remembering through time in Sinners.

I mean, if you didn’t FEEL that scene, you might want to get checked for a pulse.

You cracked this thing open, Rae. I’m blown away by the depth and brilliance of your writing, study and spirit work. Thank you for your heart, art, and generosity in illuminating all these Zora connections! ❤️ It has left me stunned and inspired.

Another brilliant piece, friend. Wow. You blow my mind. I loved learning how Zora used music to connect with people and hear their stories. Once again I really FELT all those strings throughout time, and the way music and stories have connected people across centuries. Really beautiful writing. Thank you for sharing with us.