Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the Harlem Renaissance

A Call to Step Through the Sacred Portal

When the Harlem Renaissance launched a century ago, it wasn’t just an artistic boom.

It was a portal. A tear in the veil. A gathering of voices that had always been there but were suddenly seen, felt, and impossible to ignore.

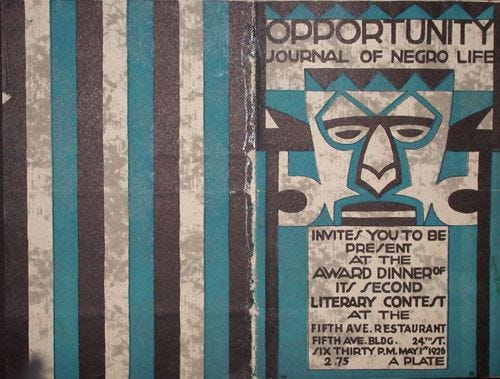

If you’re looking for the timeline coordinates, start with May 1, 1925. That night, the Urban League’s Opportunity Awards Dinner was held at the Fifth Avenue Restaurant to celebrate the literary talents of the New Negro Movement. The food? Chicken, mashed potatoes, and green peas. Not exactly a feast. But the room? The room was full of brilliance.

Langston Hughes. Claude McKay. Zora Neale Hurston. Countee Cullen. James Weldon Johnson. Charles S. Johnson of the Urban League, who had the vision to create the event. W.E.B. Du Bois. Alain Locke, the unofficial press agent of the movement, building that D.C.-to-New York pipeline of opportunity. And white patrons like Annie Nathan Meyer of Barnard College, author Fannie Hurst, and Paul Kellogg—editor of Survey Graphic—who styled themselves as progressive enough to fund the future of Black art were there too. It is worth noting that it was such a rare occurrence of integration that the Fifth Avenue Restaurant was the only venue willing to host the contest’s dinner.

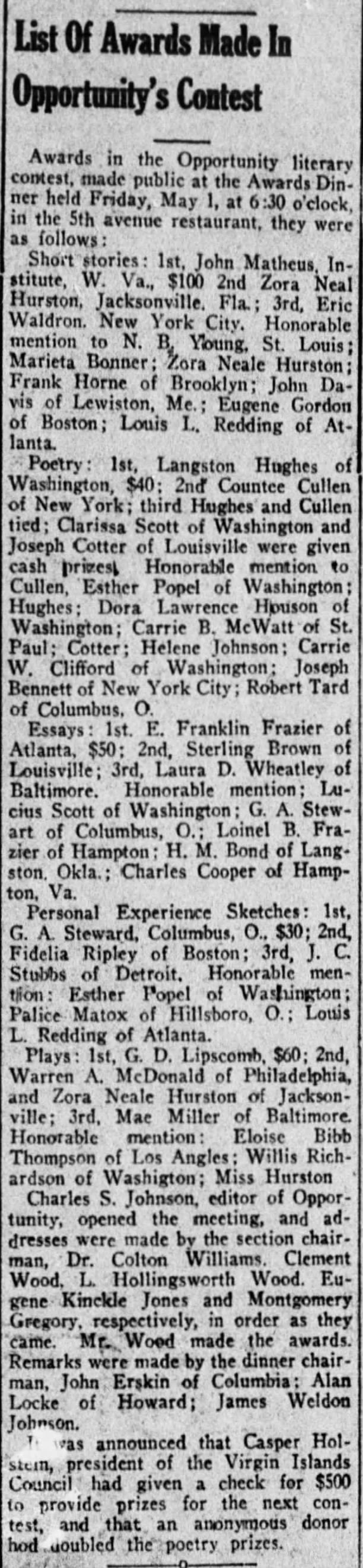

That night, thee Zora Hurston walked away with the most prizes: two second-place wins for Color Struck (play/drama) and Spunk (short story)—each worth $35—and two honorable mentions for her play Spears and her short story Black Death. She had just moved to New York earlier that year in January with $1.50 in one pocket and a whole lot of hope in the other. After having her short story (and my personal favorite) Drenched in Light published in the December 1924 issue of the Opportunity Journal of Negro Life, Zora stuffed newspaper in her suitcase to keep her sparse belongings from rattling around as she boarded the train to the Big Apple. Four months later, she was the talk of the town.

And she let it be known.

Thirty-four-year-old Zora—who had already become a master at shaving a decade off her life—walked into the afterparty (yes, the folks had afterparties back then!), flung a bright-colored scarf around her shoulders, and shouted:

“Colorrrrrrr Struckkkk!”

Like she was announcing herself on stage. She stopped the room. Some were charmed. Some were annoyed. But Annie Nathan Meyer saw something else beyond those feelings. She quickly came to believe that Zora was a woman who could withstand the pressures of being the first Black student at Barnard College.

And so she did. Zora enrolled on the Morningside Heights campus that fall in September 1925, despite the difficulty of financing such a prestigious education—or fitting in with her Southern drawl, ways, and skin color.

A week after the awards dinner, she also attended the opening of the Schomburg Center. You can still find her signature in the guest book for the event. She even wrote Arturo Schomburg a letter asking for financial support to attend Barnard. Unfortunately, he didn’t respond.

Nonetheless, all this—all of it—began unfolding for Zora within five months.

The kind of transformation we dream about as artists.

But it’s a given that we rarely consider the costs of such evolution.

Before the Boom

To understand the moment, we have to go back just a little further.

Long before anyone called it the Harlem Renaissance, there was a different kind of gathering.

On March 21, 1924, the New Negro Movement was formally—and some would say wrongfully—announced at a dinner hosted for Jessie Redmon Fauset to celebrate the release of her debut novel, There Is Confusion. What was intended as a literary evening in her honor quickly became a cultural crossroads. Alain Locke took the moment to declare that a shift was underway. This new generation of Black artists was no longer content to simply be accepted. They were ready to be seen.

Pause here to give Jessie her flowers.

She published most of the Harlem Renaissance contemporaries during her tenure as editor of the NAACP’s journal, The Crisis. My heart goes out to her when I imagine her big night being usurped for something “bigger.” Maybe I can convince Victoria Christopher Murray, author of Harlem Rhapsody (which brilliantly showcases Jessie as a fictional protagonist), to throw the lady a party of her own. Hey—I did it for Zora!

That dinner, often overshadowed in the grand narrative, was the signal fire.

From there, the current picked up speed.

Organizations like the NAACP and the Urban League began to recognize the potential of the arts—not just as expression, but as strategy. Charles S. Johnson, editor of The Opportunity Journal of Negro Life, had already begun steering the journal away from its academic roots. It had featured dense sociological articles from scholars like Melville Herskovitz and even Zora’s mentor, Franz Boas (aka the Father of American Anthropology). But Charles saw something more.

He transformed Opportunity into a literary platform, inviting fiction, poetry, and creative essays. In doing so, he helped reshape the very soul of the movement—especially since Du Bois was heavy into “art as propaganda,” which came with a lot of censorship and gatekeeping.

While we’re often taught that the Harlem Renaissance was an artistic movement, it’s important to understand that the art and the artists became the mediums through which politics breathed.

Literature became the language through which liberation was imagined.

And of course, everyone had their own ideas on how to do it.

That May Night in Harlem

By the time the awards dinner was held on May 1, 1925, it wasn’t just a celebration.

It was a culmination.

An official kickoff.

A declaration of cultural pride and advancement.

The key players were all there: Du Bois, Locke, Johnson, and of course, Zora—Zora with her scarf and her stories, ready to claim space.

That night at the Fifth Avenue Restaurant, you had to feel the shift in the room.

Even if the peas were cold.

The Renaissance did not arrive without opposition.

Even Zora, as much as we love her, endured things we rarely talk about.

She faced financial instability, exclusion from the very circles she helped shape, and a level of fetishization that cut deep. There were gender, race, region, and social politics that both created and stifled opportunity. And the colorism. If you notice, the Harlem Renaissance had a certain hue to it—which Zora fit, with her light brown complexion peppered with freckles.

Not to mention, most of the contemporaries were Northern born and raised.

Zora didn’t always speak publicly about her pain. She knew how quickly the truth could be used against her. And she understood the burden of being one of the few.

Remember: Du Bois was serious about that “talented tenth” ideology too. And plenty of folks believed him and agreed with him.

How the Harlem Renaissance Centennial Impacts Me

Zora carried it all—the possibility and the pressure.

And I think about that a lot. Especially now.

This centennial is personal for me. I’ve had the sacred honor of learning Zora’s story in ways that go beyond the archives. I’ve talked intimately with countless members of her family. I’ve stood in the places she walked. I’ve had cherished moments in homes she lived in and speak regularly with a woman who was a student in her classroom in 1958.

I’ve studied the work of scholars who spent decades keeping her name alive, and whose shoulders I now stand on.

I’ve benefited from their generosity in welcoming my self-taught approach into their rare air.

I feel the weight and wonder of that daily.

And right now, in this hundredth year, I feel a stirring in myself. A call to return to the page. To my own stories. To my own craft. To write and produce the work that is truest to me—even if it isn’t understood right away. Even if it doesn’t fit a mold.

Because Zora has taught me that the page is not just a blank space.

It’s a sacred one.

She reminds me that even if I don’t get all the flowers in my lifetime, the work still matters. The stories still deserve to be told.

The truth—no matter how complicated or unglamorous—still needs to be held.

And that as I am birthing, I get to become.

Where Do We Go From Here?

When I curated and produced the Zora Neale Hurston Summit this year, it was a living answer to that call.

Writers, scholars, thespians, spiritualists, herbalists, culture bearers, Hollywood stars, and celebrated thought-leaders from all corners of the country gathered together—not because we all fit into a single definition of excellence, but because we knew excellence could never be contained by one voice, one form, one kind of respectability.

We came together because Zora’s legacy demands that kind of multiplicity.

That kind of audacity.

In honoring her, we created our own renaissance.

And I think all the Harlem Renaissance ancestors felt it.

I think they, led by Zora Hurston’s solo, answered our call in an octave that will reverberate for centuries to come.

So I ask you now:

Will you bear the legacy of this work?

Will you tell the truth as you know it?

Will you let your craft carry you through the discomfort and into the light?

The portal is open.

It’s humming.

Step through.

And while you’re at it, remember this:

The veil between us and our artistic ancestors is thin.

Thinner than we think.

Their wisdom is not behind us. It’s beside us.

It’s waiting in the quiet hours. It’s whispering from the bookshelf.

It’s humming through a jazz record or dancing across the pages of a dusty classic.

We can call on them.

We should call on them.

Because yes, the Harlem Renaissance was divine.

But it wasn’t called that at the time.

As Dorothy West once said, they didn’t know they were part of a movement.

They were just a bunch of broke kids trying to write and make art.

And that, to me, is holy.

They weren’t waiting on a hashtag. They were answering the ache.

That quiet inner knowing that said: create anyway.

So I’m telling you now—do it.

Answer the call. Not because it’s trending, but because it’s yours.

And if you want to add another layer of magic, start tapping into what our Harlem Renaissance ancestors were making.

Give yourself over to who they were and how they were.

Read their poetry. Study their plays. Listen to their music. Examine their essays. Labor over their letters.

Get curious about their form, their genres, their range, their life experience.

Many of them risked everything to express something true, even if they didn’t always master their intention.

And now the question is:

What will we do?

What will we do to honor them?

What will we do to honor ourselves?

What will we do to move the culture forward?

The portal is open.

The ancestors are watching.

The page, canvas, and screen are hungrily waiting.

Let’s begin.

Thank you for sharing! ✨❤️

As a mother and children's book author, one way I plan on honoring her is reading children's books about her to my kiddos.